Walls

Though seemingly a mask of nothingness, heech occupied the better part of nine years of my life, during which time I made it in every shape and size. My small heech rings fit around a finger, and the largest heech could hold an adult. Nine years of working with the same figure had become so habit-forming that I might very well have fallen ill had I tried to give it up. But I also felt the need to put it aside and turn my attention to other things.

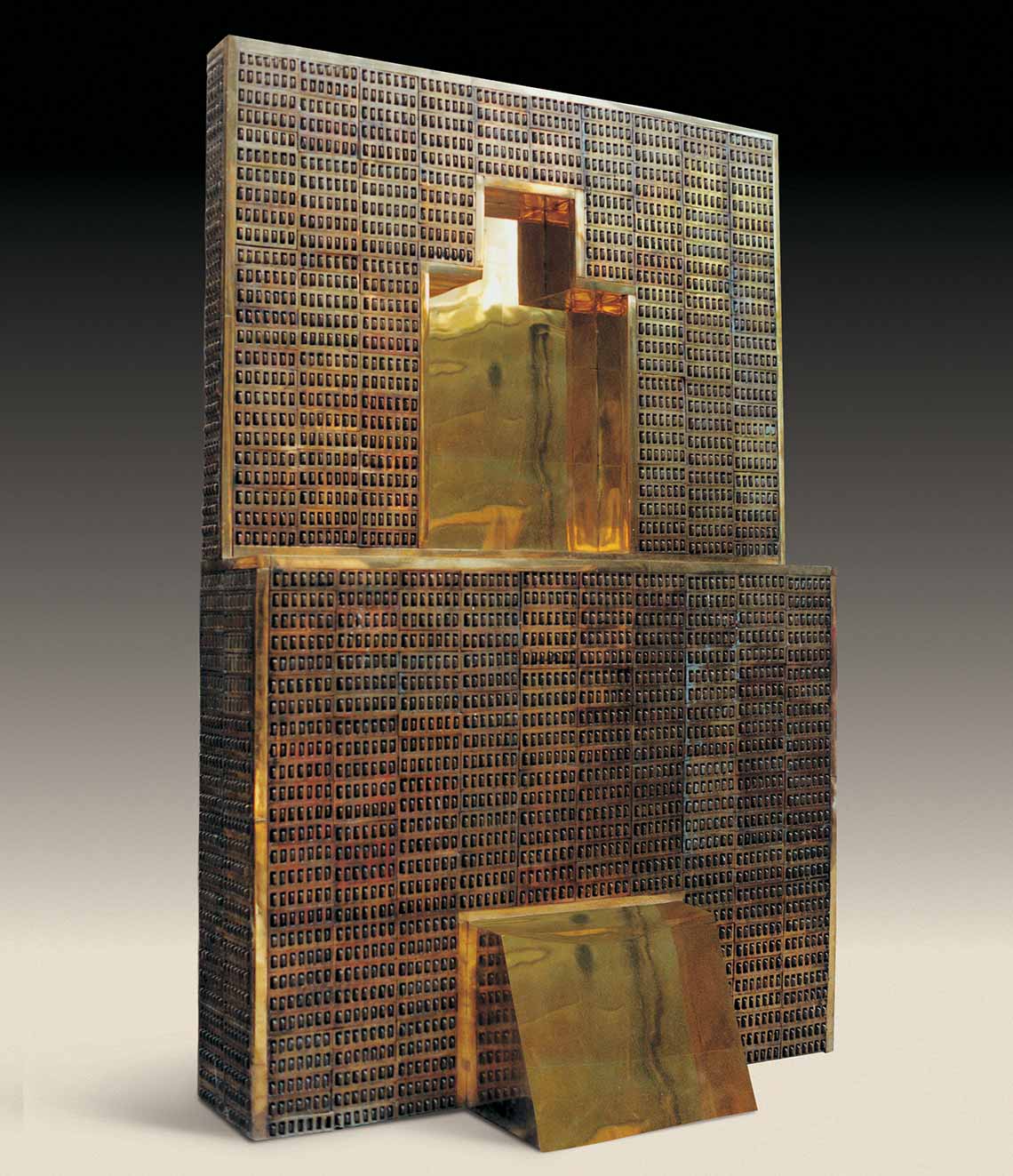

I subsequently arrived at the idea that Iran was a wall from beginning to end. Every time an Iranian builds a house or garden, he surrounds it with a wall; every rug she weaves carries a wall-like border around its periphery. What mystery lay concealed behind these borders and walls I did not know. I had other objectives in mind. For instance, I built a wall in whose shade Farhad could rest, or I provided an opening in the middle of another as an entrance for him. As a result, some of my walls began to resemble pulpits (minbars), though it was not mosque pulpits I had had in mind. To me the structure of the minbar, especially with the steps leading up to the top where the spiritual leader sits, has been a source of wonder.

The making of walls effected transformations in my working style. I withdrew into myself. Each day the idea grew stronger in me that in making walls, I should work in the same way that masons did. Like them, I wanted to build my walls by laying brick. What was more, I wanted to make the bricks myself. I considered it false to call myself a ‘sculptor’ and my works ‘sculptures.’ Neither did I feel a bond with Western sculpture, nor could I find anything to substitute for it. Instead, I preferred appellations such as ‘heech-maker’ or ‘wallmaker,’ for it was in these fields that I had attained a higher level of skill. Most importantly, my life was closer to the lives of artisans, who spent every waking hour at work, than to the lives of artists, who often consider themselves the elite of society.

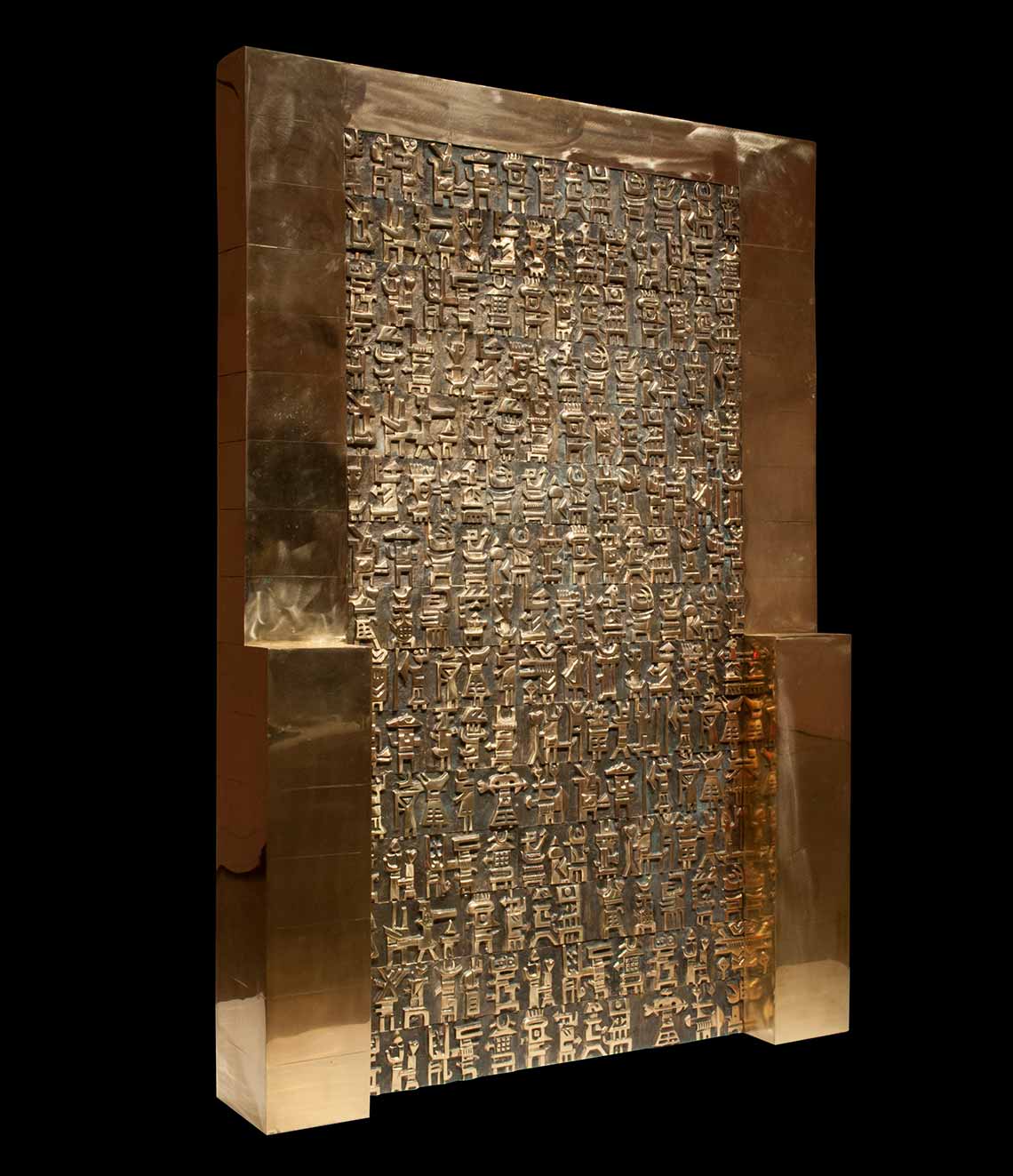

The Wall series, which includes formally the purest and stylistically the most modern works of Tanavoli. Recalling classical monuments, the Walls are basically freestanding monolithic sculptures that evidently reincarnate great ancient walls and relics of the Achaemenid or Sassanid dynasties.

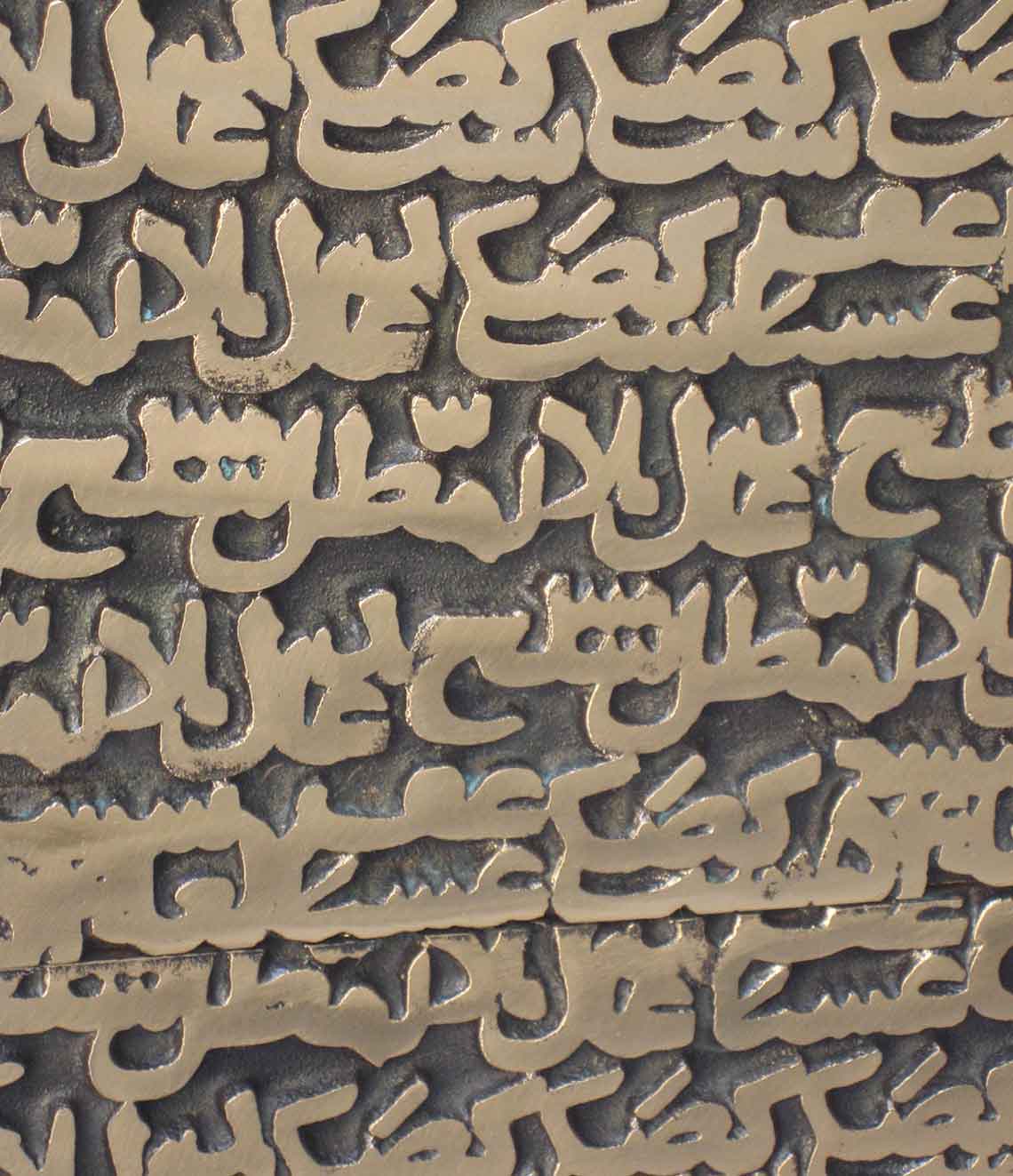

Inscribed by textual manuscripts and figurative reliefs, they are memorials to the ancient Persian civilization to which the artist pays tribute in his oeuvre. Unlike modernist sculptures, the works of the Wall series are not essentially about the volume, but actually point to the surface of the sculpture which, being decorated by dense inscriptions, evokes historic inscriptions beyond its apparent shape.