"Sculpture Meets Poetry"

By John Thomson | Galleries West

31 July 2023

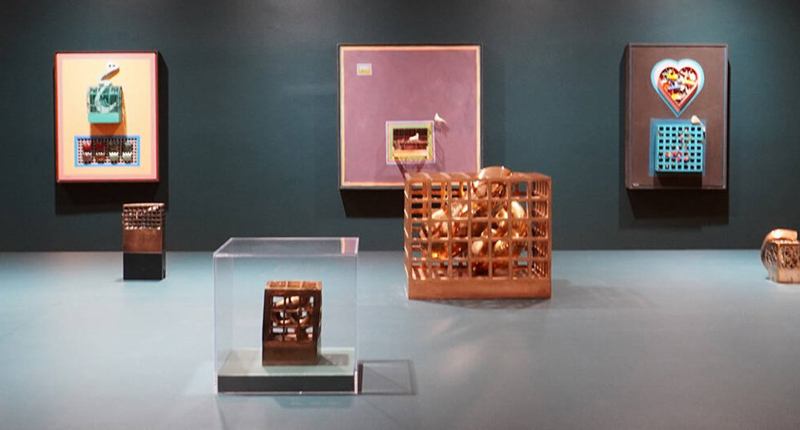

Installation view of “Parviz Tanavoli: Poets, Locks, Cages,” exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery, July 1 to Nov. 19, 2023 (photo courtesy Vancouver Art Gallery)

Installation view of “Parviz Tanavoli: Poets, Locks, Cages,” exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery, July 1 to Nov. 19, 2023 (photo courtesy Vancouver Art Gallery)

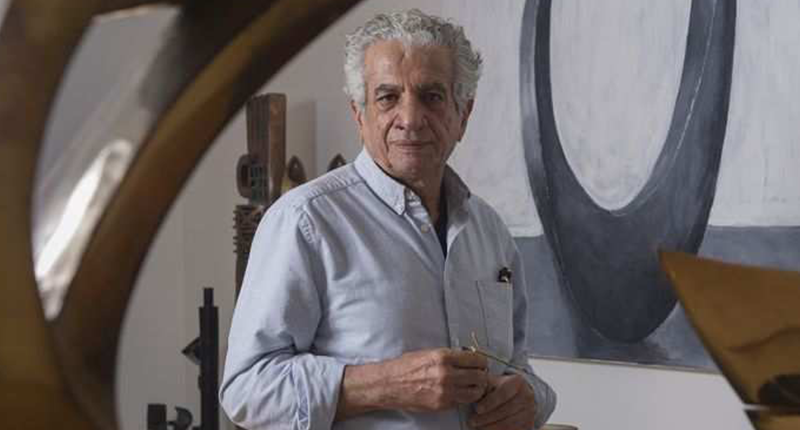

Blinded by our own conceit, it’s easy to miss what’s happening elsewhere in the art world. Poets, Locks, Cages, on view at the Vancouver Art Gallery until Nov. 19, looks at works by Parviz Tanavoli, an influential figure that the show’s curator calls the father of modern Iranian sculpture.

The exhibition includes more than 100 of Tanavoli’s works, including sculptures, paintings and drawings that encapsulate six decades of artistic practice. Tanavoli has made his home in the Vancouver area for more than 30 years, and also maintains a studio in Iran.

Parviz Tanavoli, “Poet and the Beloved of the King II,” 1963, bronze (Manijeh Collection)

Parviz Tanavoli, “Poet and the Beloved of the King II,” 1963, bronze (Manijeh Collection)

Born in Tehran in 1937, Tanavoli studied sculpture in Milan before returning home, where he helped start the influential Saqqakhana School in 1961. Dedicated to modernizing Iranian art, the movement favoured abstraction over representation.

Tanavoli’s works draw heavily on popular myths and folklore from before and after the Muslim conquest of Persia in the mid-seventh century. Inspired by history, he reinterprets ancient symbols using modern materials and abstract imagery.

Tanavoli says poetry was his first calling, but he became a sculptor instead. He views the poet he refers to in his work as a self-portrait.

“I consider my sculpture to be a form of visual poetry, the annunciation of freedom, peace and love,” he says.

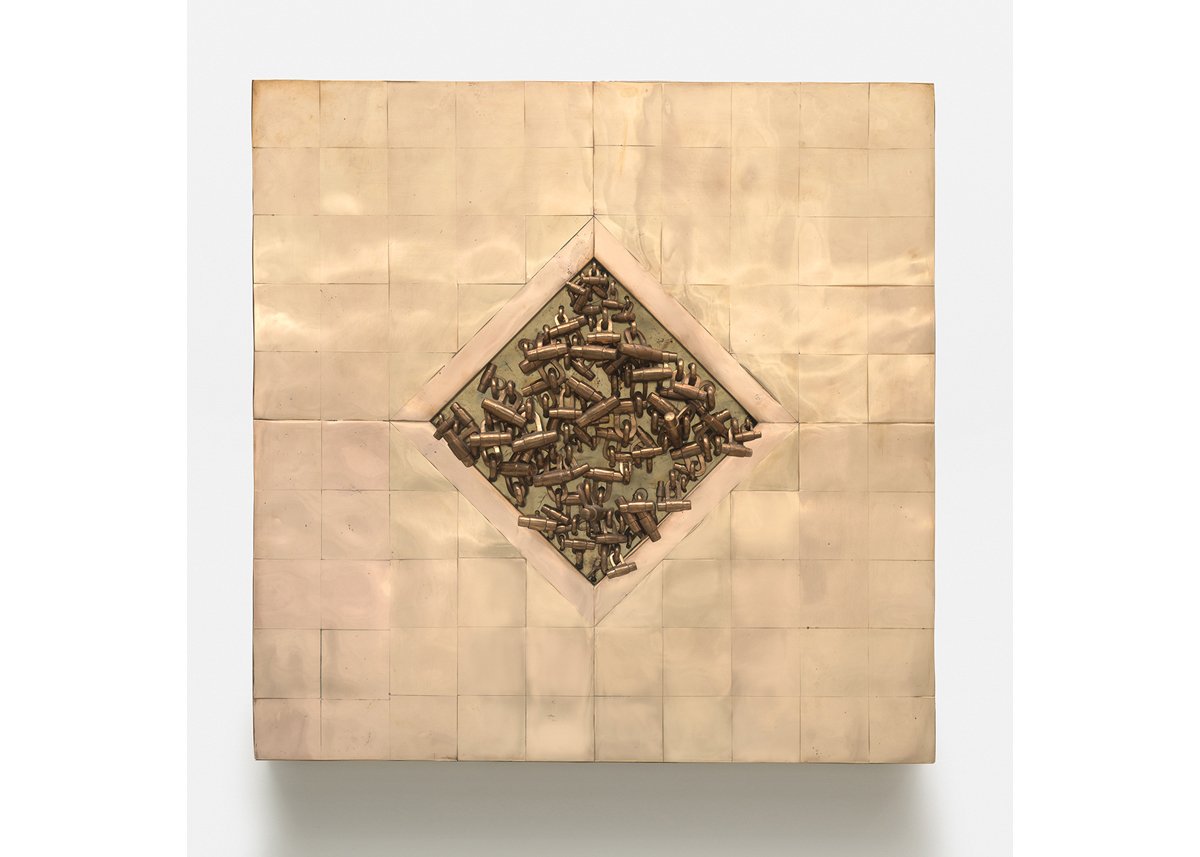

Parviz Tanavoli, “Here No One Opens Any Gates III,” 1986, bronze (Tanavoli Family Collection)

Parviz Tanavoli, “Here No One Opens Any Gates III,” 1986, bronze (Tanavoli Family Collection)

Certain themes wind through his work. Locks, which fascinate him with their mechanical complexity, are piled high in the abstract wall relief Here No One Opens Any Gates III. Tanavoli has also worked them into pieces like Poet and the Beloved of the King II.

Cages, which he considers to be places of refuge and not imprisonment, also figure prominently, often appearing together with birds, a symbol of love and healing. Grill work is also used to represent the cage, as in Poet in Love.

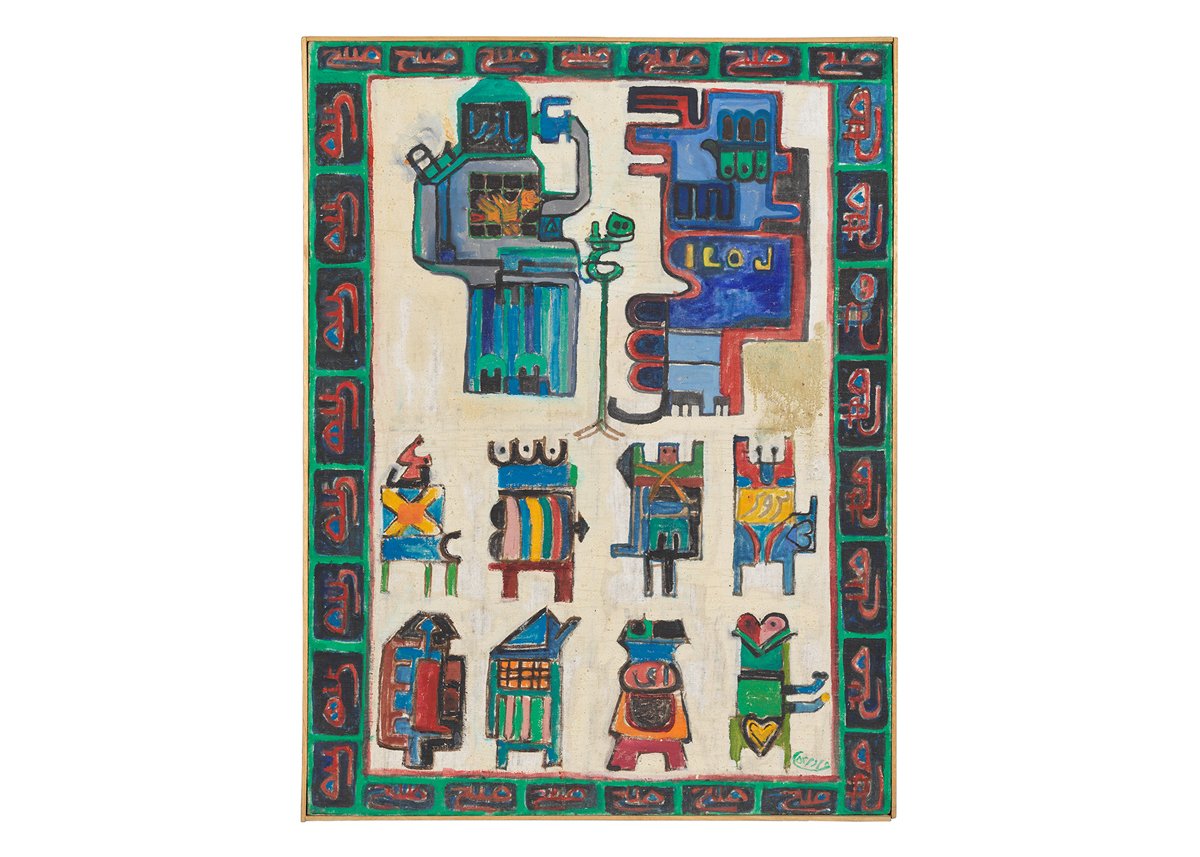

Parviz Tanavoli, “Farhad and I,” 1973 oil on canvas (Tanavoli Family Collection)

Parviz Tanavoli, “Farhad and I,” 1973 oil on canvas (Tanavoli Family Collection)

He acknowledges the old symbols but plays with them too. Look for the cheeky, ultra-modern Bird and Cage, made from neon and Plexiglas. Yes, neon. Or Poet and Arabesque, a riff on a traditional Persian design that Tanavoli has interpreted in super-bright colours reminiscent of the Pop Art era. His early paintings, such as Three Lovers, are geometric abstractions while Farhad and I, based on a revered pre-Islamic mythical character, is blockish and brightly coloured.

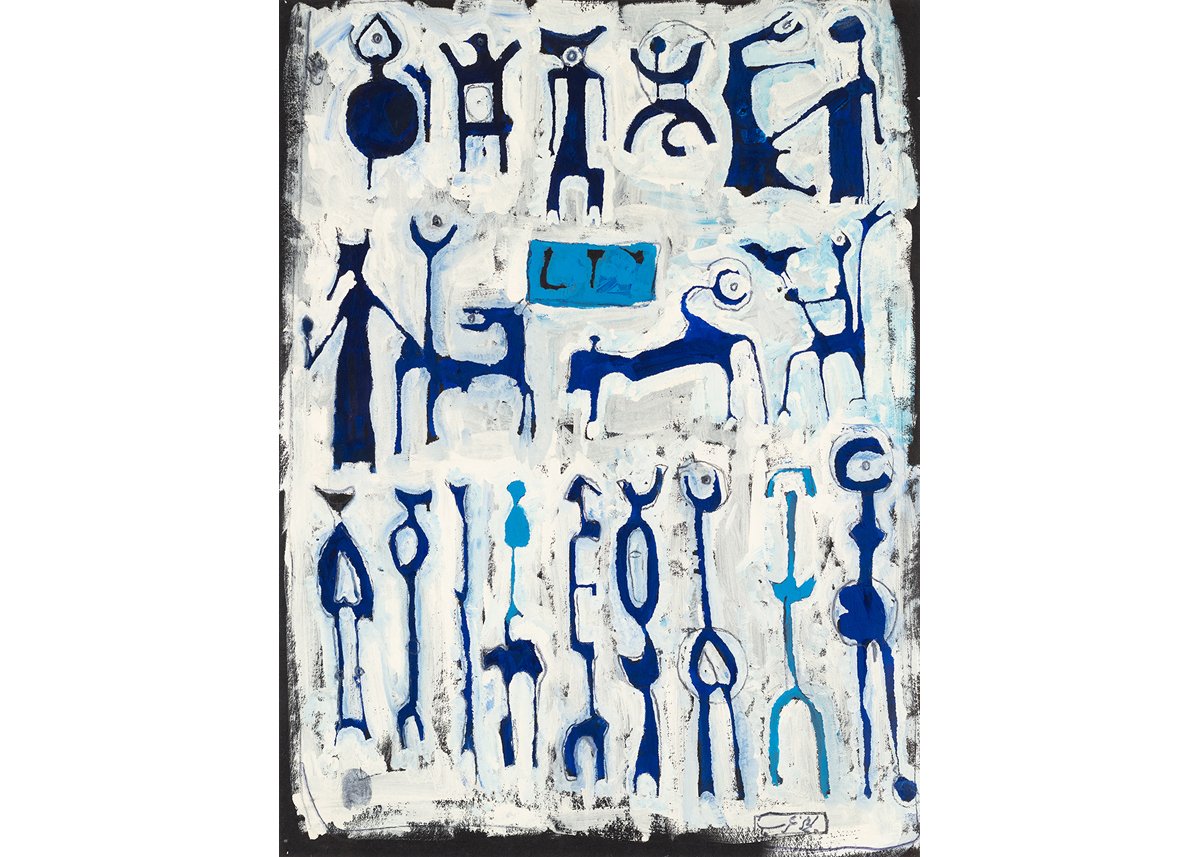

Parviz Tanavoli, “Persepolis #1,” 1961, tempera on paper (Grey Art Gallery, New York University Art Collection, gift of Abby Weed Grey)

Parviz Tanavoli, “Persepolis #1,” 1961, tempera on paper (Grey Art Gallery, New York University Art Collection, gift of Abby Weed Grey)

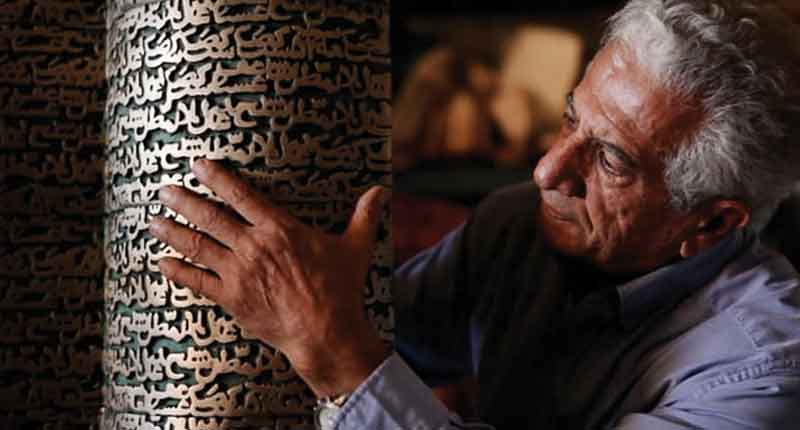

Calligraphy, another traditional art, appears as a series of humanoid figures in Persepolis #1. It is not a literal interpretation of text but an artwork to be admired in its own right. Tanavoli has assigned calligraphy a new task as design and decoration, also liberally applying it to stelae he made in the early 2000s.

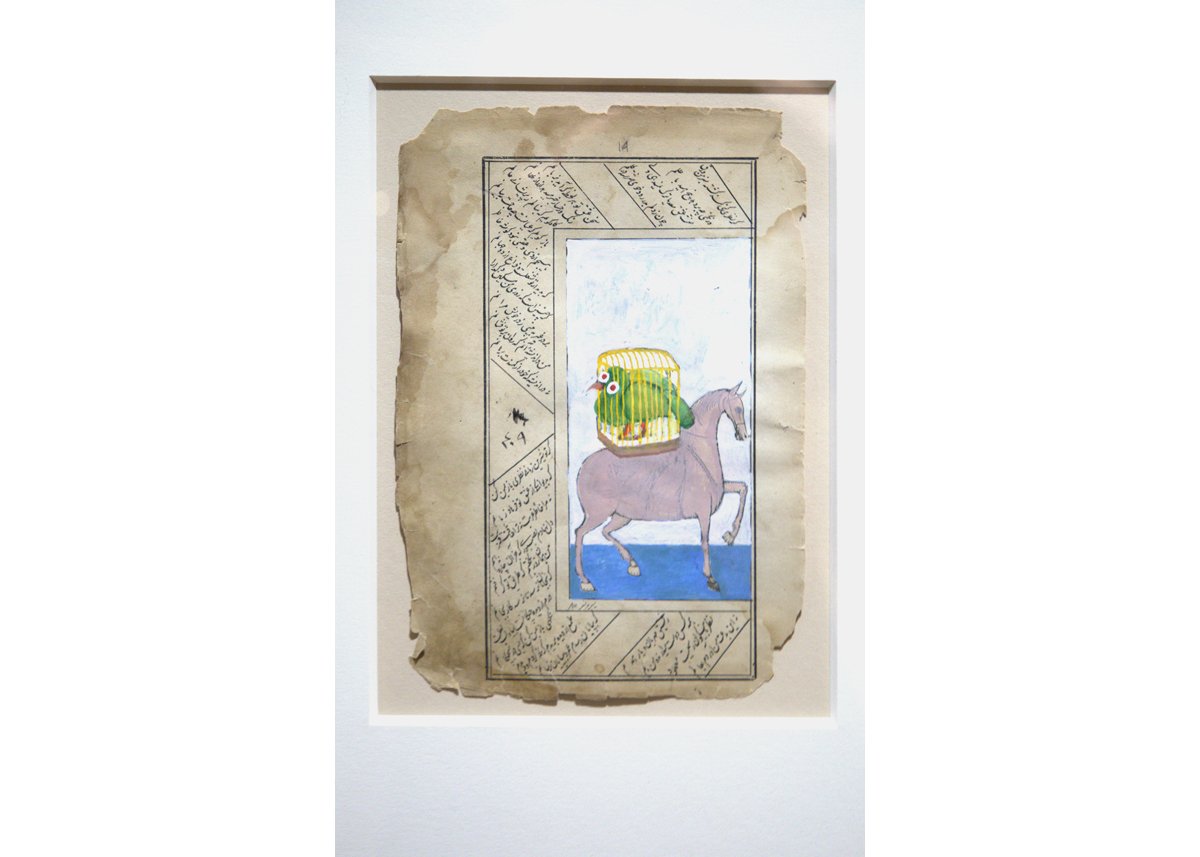

Parviz Tanavoli, “Cage Bird on Horse,” 2001, gouache on paper (photo by John Thomson)

Parviz Tanavoli, “Cage Bird on Horse,” 2001, gouache on paper (photo by John Thomson)

One highlight is Wonders of the Universe, a series of small drawings in gouache and watercolour that Tanavoli inserted into antique pages from manuscripts he brought with him to Vancouver. Most are sketches for future projects, such as Cage Bird on Horse. But there are also scenes of his new life in the West that give the ancient pages new life.

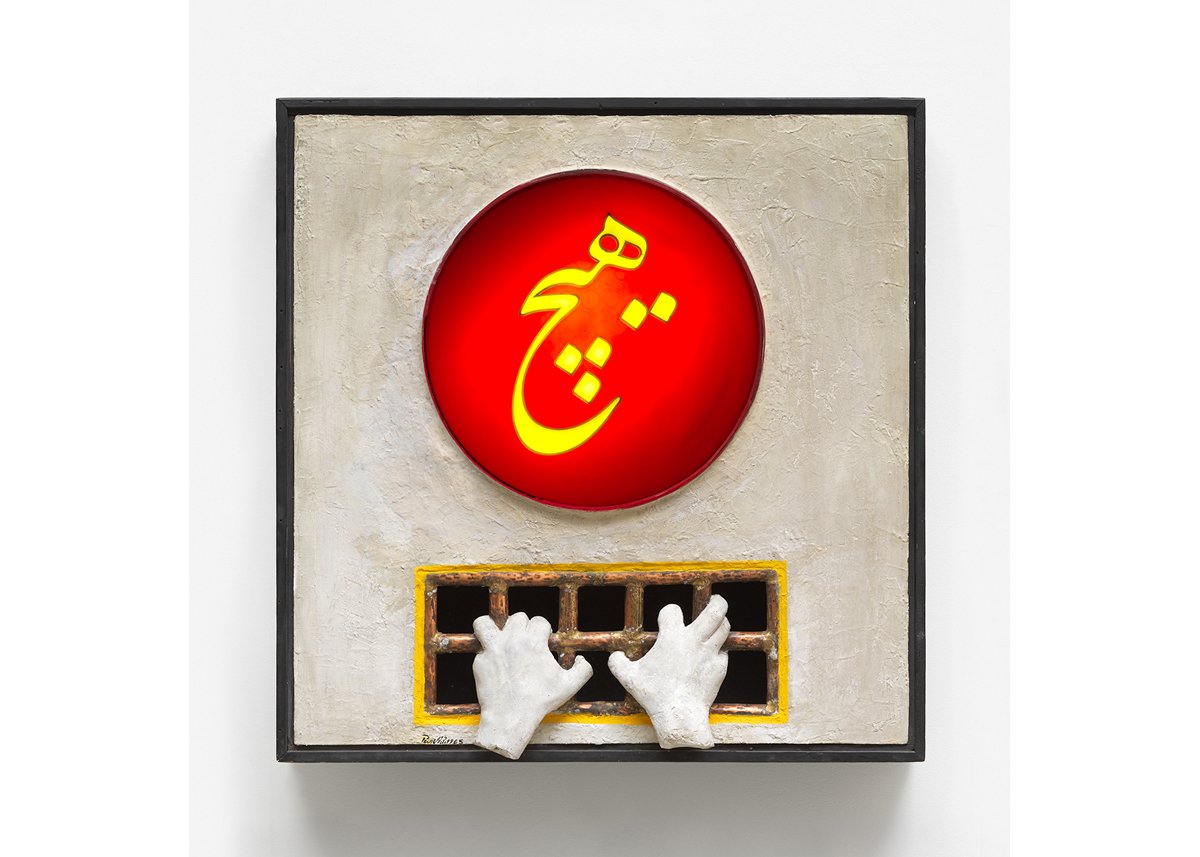

Heech, the Persian word for “nothing” deserves special attention. Rooted in the Sufi belief that nothingness is an aspect of the divine – a replacement of the ego in favour of the inner or higher self – heech is nothing but also something. The word is composed of three Persian characters that Tanavoli has combined into an abstract, ribbon-like construct.

Parviz Tanavoli, “Heech and Hands,” 1965, mixed media (Manijeh Collection)

Parviz Tanavoli, “Heech and Hands,” 1965, mixed media (Manijeh Collection)

In sculptures, such as Heech and Cage, it takes a three-dimensional form. In the mixed-media construction Heech and Hands, it becomes a statement. It’s perhaps fitting that the final sculpture, Poet Turning Into Heech, suggests that heech has enveloped the poet, who must lose himself in nothingness to find truth and beauty.

Poets, Locks, Cages is an important show. It attributes the birth of modern Iranian sculpture to Tanovoli’s melding of the sacred and the secular. While the exhibition doesn’t address politics directly, guest curator Pantea Haghighi says art responds to its surroundings and Tanavoli has always reacted to his surroundings.

“His art is about Iran, not the politics of Iran,” she says. “His legacy is his contribution to modern sculpture in Iran. Before him, it did not exist.”

To watch the Vancouver Art Gallery’s video about Tanavoli, go here.

Parviz Tanavoli: Poets, Locks, Cages at the Vancouver Art Gallery from July 1 to Nov. 19, 2023.