"Sculptor finds himself in the crossfire of Iran’s culture wars"

By Najmeh Bozorgmehr | Financial Times

27 March 2014

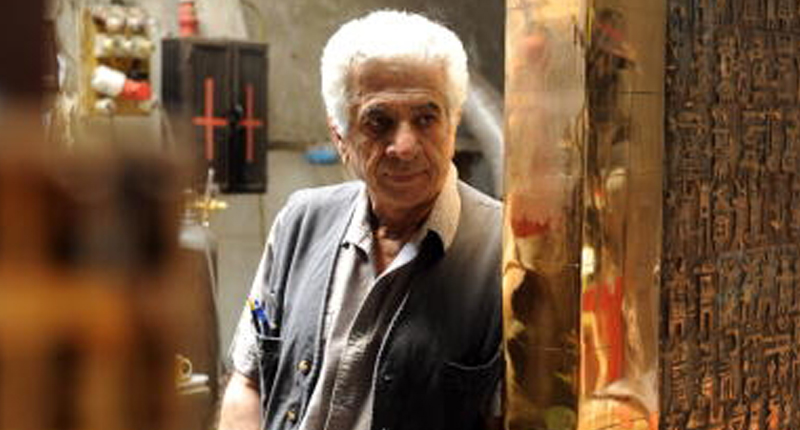

When officials from Tehran municipality broke into the house of Iran’s most celebrated visual artist to remove works they claimed were city property, they carelessly put chains around the unwrapped bronze sculptures and lifted them with cranes.

The raid on the home of Parviz Tanavoli – which damaged and broke artworks worth millions of pounds – was rooted in a decade-long dispute between the artist and the local government, but has now been dragged into a rivalry between the mayor of Tehran and the president, Hassan Rouhani.

Mohammad-Baqer Qalibaf, Tehran’s mayor since 2005, is a former commander in the Revolutionary Guards who has built a reputation for being a moderniser, winning plaudits for a beautification campaign that saw contemporary artworks displayed around the capital.

But in last summer’s presidential elections, he lost to Mr Rouhani amid well-documented hostility between the two candidates. During the campaign, Mr Rouhani infuriated the mayor, saying “I am not a colonel [referring to Mr Qalibaf]. I’m a jurist”.

Hardliners, who control the judiciary and the Revolutionary Guards, and who have power bases in the parliament and state media, are in a power struggle with Mr Rouhani’s centrist government and have taken their battle to the cultural sphere. As the president struggles to relax cultural restrictions, the hardliners warn of cultural conspiracies that allegedly undermine the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Mr Qalibaf’s continued anger over the election campaign has added another institution to the list of Mr Rouhani’s opponents, say analysts.

“Tehran municipality has also joined those power centres which are determined to weaken Rouhani by preventing him from achieving anything tangible in cultural fields,” says one reform-minded former official.

The attacks on Mr Rouhani’s cultural policies come as hardliners are being reined-in on the nuclear issue by Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who does not want to sabotage nuclear negotiations with western powers.

But the ayatollah does not extend his control to other fields, and has even joined critics of the government and warned against excessive cultural freedom on which Iran’s “enemies [the west] have concentrated”.

“We cannot sit idly and say it is ‘freedom’ if some exploit art and speech . . . to attack people’s religious beliefs and infiltrate Islamic and revolutionary culture [to damage it],” Ayatollah Khamenei said last week. “Such freedom does not exist anywhere in the world.”

Mr Rouhani’s government has so far relaxed restrictions on the cinema industry and allowed a leading publisher to reopen. But the president has been prevented from instituting many other reforms. Social networks such as Facebook and Twitter remain filtered; renowned novelist Mahmoud Dowlatabadi still cannot publish his novel The Colonel, which is about the Islamic revolution; and a reformist newspaper, Aseman, was shut down by the judiciary less than a week after it launched.

When Mr Tanavoli woke last week to the screams of his daughter, who found more than 20 strangers in the family’s garden and a line of trucks and cranes in the street, he was unaware of the politics behind the intrusion.

“I think they [municipality officials] do not like my works and do not understand them, but probably think of the money they can generate,” he says. Mr Tanavoli is well-known for his heech (“nothing”) sculptures, symbolising his ambivalence towards the past and present.

Even if political calculations were involved, he says, Iranians’ longstanding rejection of state-sponsored art, books and films, means such suppression will not change anybody’s opinion.

The artist’s dispute with the city has been entangled in politics since Tehran municipality, then run by reformists, bought Mr Tanavoli’s house more than a decade ago. The large villa in the affluent Niavaran neighbourhood has a fine Iranian brick façade and a modern interior, and was turned into a museum where 57 of Mr Tanavoli’s works were on display.

But when Mahmoud Ahmadi-Nejad, the former president, became mayor of Tehran in 2003, he immediately ordered the museum to close. Mr Tanavoli took back his house after a five-year lawsuit.

The judiciary has yet to rule on the sculptures, which Mr Tanavoli insists he sold to the municipality on condition they were displayed in his museum. The court ordered that the artworks remain with the artist until a final verdict is issued.

Mr Tanavoli says he is puzzled that the judiciary did not revoke its earlier decision before it issued a new decree allowing municipality officials to take the sculptures.

Despite the tussle, Mr Tanavoli says he has “not at all” lost hope in Mr Rouhani and insists repression will not push Iran’s culture backwards.

“They [the hardliners] created concepts like ‘holy cinema’, ‘holy literature’, and ‘holy art’, none of which became popular, but you see, visual art has flourished without any state support,” he says, shrugging off the dispute over his works. “I will turn my house into a private museum.”