"New Documentary Honors Father of Modern Iranian Sculpture"

By Hadani Ditmars | Middle East Institute

7 March 2016

At the edge of the Pacific, in a bucolic suburb of Vancouver called Horseshoe Bay, the “father of modern Iranian sculpture” has lived a quiet existence since 1989.

Despite being a pioneer of Iranian modernism and one of the founders of the Saqqakhaneh School of Art in mid-20th century Tehran, Parviz Tanavoli has been virtually invisible in Vancouver.

Today, however, a new documentary about the artist directed by Canadian filmmaker Terrence Turner has bridged the chasm between the Middle East and the Pacific Northwest.

When Poetry in Bronze screened recently in Vancouver, home to 40,000 Iranians, Tanavoli was celebrated by a whole new generation of young Iranian-Canadian artists inspired by his example.

“I felt honoured by the film,” Tanavoli said from his home in West Vancouver. Noting the centricity of Persian culture in his work, Tanavoli felt that Turner “had honoured my heritage and tradition … you cannot divorce my work from Persian culture.”

It was the idea of revealing Vancouver’s hidden jewel that inspired Turner to make the film, hoping to raise Tanavoli’s profile in his adopted land.

“When I first learned about Parviz Tanavoli, a few years ago,” explains Turner, “I was overwhelmed by how beautiful his work was, especially his bronze sculptures.”

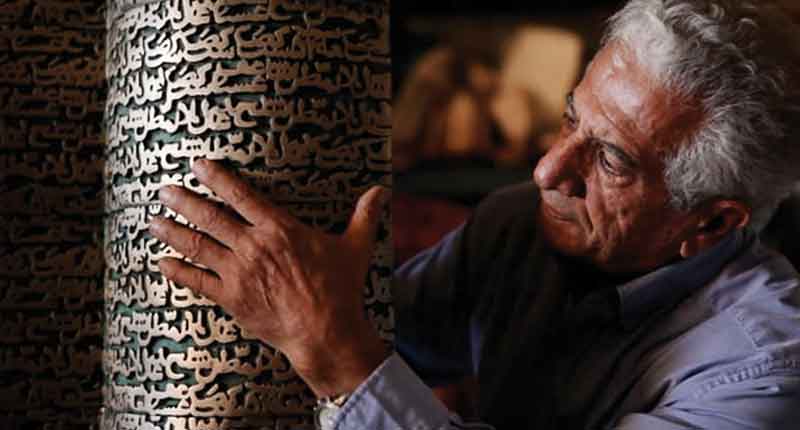

Tanavoli was the creator of a new aesthetic language that married everyday objects with ancient traditions and pop art sensibility.

Turner was also curious “about how such an important modern artist from Iran could be virtually unknown in Vancouver… It was like having Henry Moore live and work in your neighborhood, yet nobody knew he was there.”

While his work has been shown at the Tate Modern, the British Museum, the Grey Art Gallery in New York, and the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, he’s only had a single work shown in Vancouver in the 2014 Safar exhibition at the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia.

A reflective film that traces his work from the early days of his patronage by Empress Farah Pahlavi, his wily post-revolutionary survival tactics, and his mentoring of a new generation, Poetry in Bronze is also a timely reminder of the power of art in transcending cultural and political differences.

In the film, Tanavoli explains that by embracing the aesthetic of everyday objects and rejecting classicism, he hopes to become “a poet who can express himself in three dimensionality.”

Indeed, Tanavoli’s genius was in adapting modernism by working with tools and objects from his own culture. These included religious talismans and common utensils.

The Saqqakhaneh movement offered a new pictorial language and Tanavoli’s work plays on the tradition of the faux Kufic script with his own invented cuneiform—like figures that imposed a totally new narrative.

This can be seen in his Persopolis series of bronze sculptures, which reference ancient Persian tradition and embody a new artistic reality. He also painted lovers and crafted animal and human sculptures not traditionally associated with high art.

“I invented an anatomy,” explains the artist in the film, “of proportions that were not the same as Renaissance anatomy, and this was not received or welcomed by Iranian galleries. But I was fascinated by it.”

Tanavoli tread a fine line between art and blasphemy, the sacred and the quotidian. As he says in the film, “In Islamic culture, when the face was prohibited, artists used hands [to convey expression].”

In fact, his first major show in Tehran in 1965 at the Borghese Gallery had to be shut down because his use of a traditional toilet ewer was deemed ‘obscene’ by the local elite.

As Tanavoli said in an interview, “I was fed up with pretty art, pretty women, pretty objects, [and] pretty paintings. I wanted to show that what we are ashamed of in our daily life could be art.” To that end, faucets, locks, pieces of textile, old shoes and mattresses, and a variety of found junkyard treasures became his palette.

Despite threats from outraged notables to burn down the Borghese Gallery, Tanavoli soon enjoyed the patronage of Empress Farah Pahlavi. The wife of the Shah collected Tanavoli’s sculptures as well as his one-of-a-kind jewelry, often in the shape of Persian calligraphy for heech (nothingness)—a prominent theme in his work. The artist’s concept of heech was more aligned with Sufism than Sartre, and its mystical philosophy still imbues Tanavoli with a certain serenity that is conveyed both in person and in the film.

He seems to have maintained this serenity throughout his life and career, his patronage by a queen, his post-revolutionary internal exile—in which he dedicated himself to the study of tribal rugs among Iran’s nomads—and his virtual escape to Canada in 1989.

In 2002, during the reign of President Mohammed Khatami, Tanavoli was invited back from his Vancouver exile to hold an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tehran. The then Mayor of Tehran Malek Madani invited Tanavoli to turn his home into a museum dedicated to his work. A formal opening ceremony was held, attended by dignitaries and diplomats, but after a few months hardliner Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was elected mayor and closed down the museum.

The harassment by Iran’s conservatives didn’t end there. In an afternoon raid on his house in 2014 by government hardliners, several of his works were confiscated, and many of them were damaged in the process. The artist is still fighting in Iranian courts to have his work returned.

Despite the endless hurdles, Tanavoli’s dedication to teaching a new generation of Iranian artists persevered, even as it earned him the scorn of Iranian expats in the West who accused him of complicity with the regime. Through it all, Tanavoli has continued to create and works daily in his studio. He has never lost his love for art and his joy in life.

He is excited about Iran’s future under moderate President Hassan Rouhani, and anticipates “many changes” including more freedom of expression. “I’m very optimistic about the recent elections. It’s as if the people were waiting to exhale and now they can breathe again.”

Young Iranians like his students, he says, “carry the destiny of Iran in their hands. They want more freedom, better relations with the rest of the world and to be part of the international community again. They’ve been struggling for years for this and now they can almost taste it.”

Many people in the West misunderstand the essence of Iranian culture, says Tanavoli. “You cannot judge Iranian culture on the basis of the last 30 years of political history. You have to go back into the past and look at Persian contributions to science, medicine, literature, poetry and art.”

To that end, Tanavoli’s next project is another exhibition in Tehran this fall on the theme of the lion in Persian art. The artist has been collecting sculpture, tribal art and rugs depicting lions for years and incorporating them into his own work.

It will be a fitting theme for the artist’s autumnal homecoming, for Tanavoli is nothing if not a lion of Iranian art.