"Parviz Tanavoli: The Leading Iranian Artist Who Calls Vancouver Home"

By Leah Sandals | Canadian Art

11 October 2016

Parviz Tanavoli’s huge Horizontal Lovers (2016), on show at the Aga Khan Museum

Parviz Tanavoli’s huge Horizontal Lovers (2016), on show at the Aga Khan Museum

After 27 years in Canada, a public-art breakthrough.

That is what leading Iranian artist Parviz Tanavoli—who, since 1989, has been based half of every year in Vancouver, though you’d hardly know it from his low Canadian profile—is enjoying right now.

Tanavoli’s massive bronze and stainless-steel sculptures Poet in Love (2009), Big Heech (2014) and Horizontal Lovers (2016)—the latter, his largest work to date, never before seen in public—have just been installed on the grounds of the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, where they will remain until April 2017.

“This is like the beginning of an era, to have some of my larger pieces installed in public” in Canada for an extended period of time, Tanavoli says. “I’m very happy.”

Internationally, Tanavoli has been celebrated for decades. Last year, he was included in the Tate Modern exhibition “The World Goes Pop.” The Guardian has called him “Iran’s most renowned living artist and the most expensive Middle Eastern artist at auction.” His work is in the collection of the Met and the MoMA in New York, among other big museums. And he is widely cited as a pioneer of the Saqqakhaneh movement of the 1960s, recognized as the first school of Iranian Modern art.

Recently, Tanavoli—a dual Iranian-Canadian citizen—sat down to talk. Here are eight of the insights that he shared from his six-decade career.

Poetry Combined with Architecture Creates Sculpture

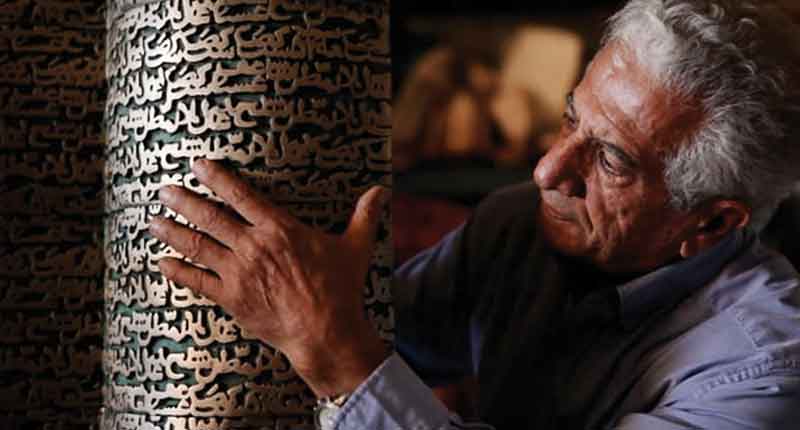

Tanavoli is perhaps best known for sculptural works, which are “based on a mixture of Islamic architecture and Persian poetry.”

“Iran is a country of poets,” says Tanavoli. “We have great poets.” (Rumi, Khayyam, Nizami and Hafiz are among his favourites.)

In fact, early on, Tanavoli wanted to be a poet. But then he went into studying sculpture, first at home in Iran and later in Italy. And he encountered a problem: there wasn’t much in the way of a sculptural tradition in his home country to draw upon.

“After Islam, our sculpture was prohibited and we stopped making sculpture,” Tanavoli explains. “But all those who were working in three dimensions turned their artworks into utilitarian things—locks, doorknobs, incense burners and so on.”

“All I found was poetry and architecture,” Tanavoli says. “And I thought, that is good enough for me.”

For instance, his Horizontal Lovers works, an example of which is installed at the Aga Khan grounds, relate in large part to Persian poetry.

“Our literature is full of love stories, and I was always fascinated by those love stories of Iran,” Tanavoli says. “From the beginning, I made double figures together,” but ones that were more “architectural and geometric” from the lovers seen in Persian-miniature painting.

Carving Marble Can Ruin Your Music Career

If he hadn’t become a sculptor, Tanavoli says he likely would have become a musician or a composer.

The door closed on that career option, though, when Tanavoli started learning how to make sculpture.

“Music, I had to stop, because my fingers were not following me anymore,” Tanavoli says. Trained initially as a violinist, he found that the marble-carving lessons were stiffening his fingers.

Today, though, listening to music remains an important part of his process in the studio.

“I like Persian classical music very much,” Tanavoli says. “I like 18th and 19th century—Vivaldi, and sometimes Mozart.”

Not allowed in his studio playlist anymore? Rap, and rock and roll.

“Because I work with music, and music is played all the time in my studio, the music changes my rhythm,” Tanavoli says. “I want to be mellow, so it doesn’t pound in on my head.”

All Art Takes Longer to Make Than You Think

Production-wise these days, most of Tanavoli’s large-scale sculptures, like the ones currently on view at the Aga Khan, take a year or two make.

But really, the timelines are a lot longer, the artist says.

“A sculpture might take a year—like Poet in Love,” says Tanavoli. “But really that is a year plus forty years—because it doesn’t come out of the blue. It’s the follow-up of all the experience you have gained for the last 40 or 50 years.”

Though inspired by the deep feeling in music and poetry, Tanavoli’s studio process tends to be methodical and judicious: sketchbook to maquette to approval to large-scale foundry work.

“Even now, I don’t have the guts to do a large sculpture out of the blue all at once,” Tanavoli says. “I have to make sure the maquette is approved, the armature, the scale.”

Expressing Yourself through Art Can Be a Challenge—Especially in the Social-Media Age

Through his work as a teacher and mentor, Tanavoli has influenced hundreds of younger artists, particularly in Iran.

When asked about the biggest challenges a younger generation of artists faces, Tanavoli pinpoints issues around expression.

“This is the hardest part of art—you may learn all the techniques, and all the craft. But how to express yourself? That is not easy.”

Tanavoli says that many of his discussions with younger artists and assistants revolve around pinpointing which of their ideas are worth pursuing and expressing in their work.

But how can a generation (make that generations) renowned for expressing themselves with abandon on social media really have problems expressing themselves in art?

“Maybe that is the reason they cannot express themselves in other [art] media—because they express themselves in all the electronic media these days,” Tanavoli speculates. “When you express yourself in electronic media, the emotion is in words, and everybody uses words. But if you have to express yourself by plaster or by steel, then you have to go to the other side of the words completely—become abstract, and not literal anymore.”

It Is Possible to Make Something from Nothing

One of Tanavoli’s most famous bodies of work has to do with the heech—a word which means “nothing” or “nothingness” in Farsi.

Since 1965, Tanavoli has made sculptures large and small of the calligraphic script of heech. These representations have ranged, as a recent retrospective at Massachusetts’s Davis Museum put it, “from delicate jewelry to polished bronze and hi-gloss fiberglass sculpture.” (Of the three works currently installed outside the Aga Khan in Toronto, Tanavoli’s 12-foot-high stainless steel Heech is likely the most striking.)

The heech can be read, in some works, as an abstract shape; in others, it is an anthropomorphized character. And its variable, all-encompassing nature is part of what keeps Tanavoli returning to it.

“Heech is the ultimate last word,” Tanavoli says. “Heech is not only nothing; it is everything. Everything at the end becomes nothing.”

The heech also connects to Tanavoli’s interest in poetry.

“This business of nothing has occupied the poets for centuries,” Tanavoli says. “Khayyam says ‘Don’t forget that all things are nothings.’”

So the heech is like the flipside of everything?

“Yes, the other side of everything,” says Tanavoli. “Instead of making everything, I decided to make nothing—because that corresponds to everything.”

Even Apolitical Artists Can Have Political Artworks

“In my art I try not to become involved with politics,” Tanavoli says—but he also admits, “I don’t know if any artist could not be influenced by the politics of his time.”

Case in point: when Guantanamo opened, Tanavoli created a small version of a heech in a cage—a sketch for what he later hoped might become a large sculpture honoring the people of Afghanistan.

“When Guantanamo opened, it bothered me a lot,” says Tanavoli. “I decided to make a monument to them. I thought, if even one of them is innocent, that is not fair.”

The big sculpture that Tanavoli was hoping for still hasn’t come to fruition—“I couldn’t find a sponsor for it, I couldn’t find a location, and I couldn’t realize it,” he says.

But the idea for a large, monumental, commemorative sculpture still exists in his mind, and related works featuring a heech in a cage are in the collection of the British Museum, among others.

Vancouver Might Be Paradise

Tanavoli and his family arrived in Vancouver from Iran on July 22, 1989.

When asked about that day, and what he remembers of it, Tanavoli had this to say:

“It was not an easy decision to leave everything behind. But we had to leave everything behind—a house, a studio. I wasn’t able to continue in Iran. I was not given a chance to work. I was not allowed to send out my artworks. I was not allowed to exhibit. I was on a blacklist everywhere.”

“My children were about to go to college and they didn’t have a chance to go, especially my two girls.

“So we had to make a big decision. And we came to Canada. And the minute we landed my wife thought, ‘My gosh, this is paradise!’

“We came here in July; the whole town was in flower. It was like a greenhouse. The air was good. The weather. Everything was so favourable. We all took it for a good omen. And then everything worked out.”

Don’t Take Local Reaction to Your Art as the Final Word

Asked today for his further thoughts on Vancouver, and why he remains based there for half of the year, Tanavoli is reflective.

“I create most of my work in Vancouver. But I don’t have any interest there for my artwork. But Vancouver is a good place for family life, and family life for me was really a priority; it was very important. And of course, I was aware of Toronto and New York and elsewhere. But we decided to go and have a peaceful family life.”

(Peace is indeed important to this man, who while being increasingly embraced in his native Iran, also encounters problems there, like detainment related to a passport issue in July.)

He adds, “You know, I still get out here and there”—which is an understatement, of course.

Next year sees an exhibition of Tanavoli’s jewellery-scaled works opening in London in April, and a solo show at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art opening in July. He just released a book, European Women in Persian Houses. His media clips continue to pile up, including coverage in Vanity Fair and Wallpaper*, and a documentary about his work, Parviz Tanavoli: Poetry in Bronze, remains available for viewing on Vimeo for a small fee.

But all through Toronto’s fall and winter, and part of its spring, Parviz Tanavoli’s Poet in Love and Big Heech and Horizontal Lovers will watch over Canada’s largest city. If you’re in the area, make sure you return the favour, and seek them out.