"Iranian artist Parviz Tanavoli’s solo US show"

By Gareth Harris | Financial Times

15 November 2015

Tanavoli’s ‘Neon Heech’ (2012)

The Tehran-born sculptor talks about the meaning of his famous ‘heech’ symbol that is the bedrock of his art

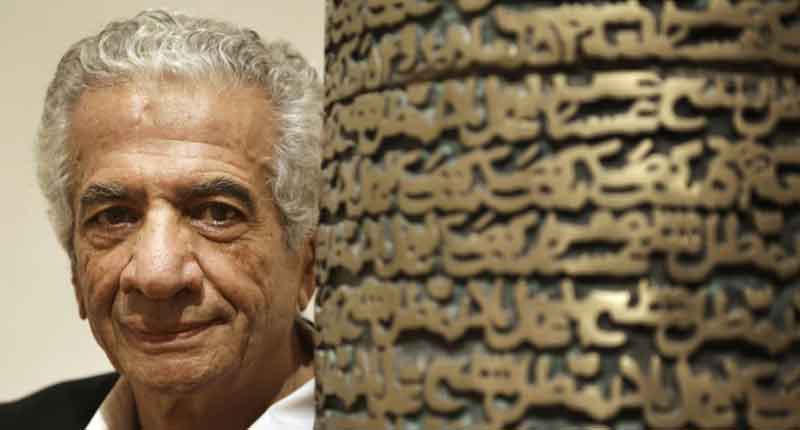

Fact after revelatory fact spills out of the Iranian artist Parviz Tanavoli. The 78-year-old, Tehran-born sculptor, scholar and polymath is ruminating on his life and work during an absorbing Skype chat from his home in Vancouver.

He describes, for instance, how in 1962 he put together a contemporary Iranian art exhibition tour of the US, which opened in Minneapolis.

“People there only thought about Persian miniatures; they had no idea that there were modern artists in Tehran,” he says. Participating artists included Charles Hossein Zenderoudi and Nasser Ovissi. “I chose the works, rolled them up and took them to Minneapolis.”

Then, in 1965, Tanavoli rocked the Middle Eastern art scene by including “Innovation in Art” in an exhibition in Tehran. The work, comprising a metal pitcher adorned with rainbow stripes inserted in the centre of a Persian carpet, was made with a Duchampian flourish. “I probably wanted to shock Iranian conservatives because they liked fine art and flowery paintings,” he says. The piece is now in the collection of the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi.

His inquisitiveness is endearing; he has a predilection for ancient Persian stone lions and tombstones made for kings of the Qajar era (1796-1925) and, crucially, a love of locks, which has informed his sculptural forms since the 1960s. “I have around 1,000 examples, mainly Persian, from pre-Islamic to the 19th century. As a child, I saw these locks hanging on the grilles of the [Shia] shrines,” he said.

Shiva Balaghi, a visiting scholar at Brown University in Rhode Island, has organised a retrospective of Tanavoli’s work, which opens next week at the Davis Museum at Wellesley College in Massachusetts.

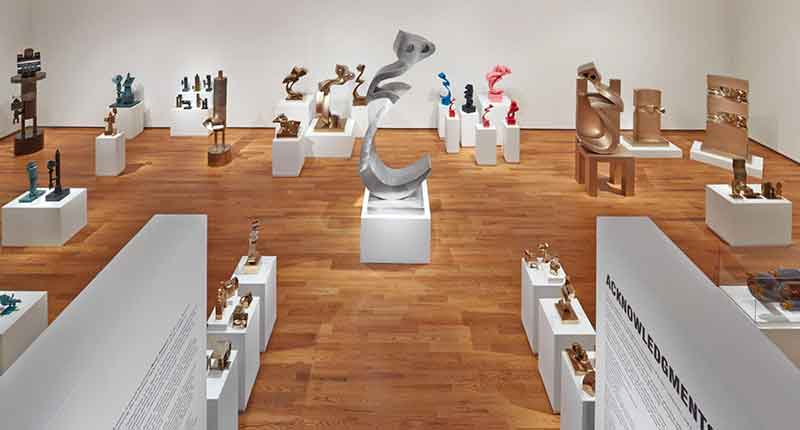

Balaghi and her co-curator, Lisa Fischman, the director of the Davis Museum, have brought together more than 175 items from the 1950s to today, encompassing prints, paintings, linocuts, jewellery and ceramics. Many works are drawn from Tanavoli’s vast private holdings; some are on loan from public collections such as the British Museum and New York University’s Grey Art Gallery. Sixty years of work will surround a centrepiece garden dedicated to Tanavoli’s “Heech” objects. “Heech”, the Farsi word and symbol for “nothingness”, is the bedrock of Tanavoli’s art. He says of its sensuous, elongated form that “Heech has a body, a shape, but also a meaning behind it”.

Tanavoli made the first manifestation of “Heech” in 1965, when he painted the calligraphic notation on to a mixed-media piece shown at the Borghese Gallery in Tehran. He explains: “I was fed up with artists misusing calligraphy in painting. Other artists were proud of following western art. So I decided to make something of nothing . . . poets, such as [the 13th-century Iranian mystic] Rumi, draw attention to ‘nothing’ centuries before me. There are things and ‘no things’, they balance each other.”

Its many iterations, especially the Heeches confined in cages, are startling, even moving. In 2005, he created a small sculpture in this vein to highlight the conditions of the prisoners held at Guantánamo Bay. The show will also include the biggest ever example, the 11ft high “Heech on chair” (2009). Tanavoli is frank, though, about the limitations of this form. “After seven years of making nothing but nothing, I decided to move away from these old friends. Somehow the Heech prevented me from moving on,” he says.

He began exploring other key themes in the 1970s, focusing on the metaphorical idea of “Iran’s walls”. These bronze monoliths, started in the 1970s, are inspired by ancient reliefs from Persepolis and Naqsh-i Rustam in Iran’s Fars province. But clearly there was no escaping his obsession with the Heech: “The Wall and the Heeches” (2015), on view in this show, comprises two Heech sculptures in a bronze slab, neatly combining the artist’s principal conceptual pursuits.

Another exhibition highlight, the oil on canvas, “Farhad and the Nightingale II” (1974), gracefully fuses the eponymous mythical Persian sculptor and a songbird. “In the chest of every poet there is a cage, and in that cage there is a nightingale singing,” the artist says. His “Neon Heech” (2012) shows mastery of yet another medium.

“His art is not just about Heech, there is much more to him than simply ‘nothingness!’ ” says Maryam Eisler, the London-based patron and Wellesley College alumna and trustee who is the driving force behind the show. It comes under the umbrella of the ambitious new initiative Eisler has launched with her husband Edward that will fund an interdisciplinary programme at Wellesley.

Eisler, who is herself loaning “Big Heech (red)” (2002), says Tanavoli’s work makes her wistful. “I left Iran permanently in 1978; seeing his sculptures brings back childhood memories of visiting the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art,” she says. Her reminiscence underlines how Tanavoli’s life and work dovetails with Iran’s tumultuous trajectory before and after the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

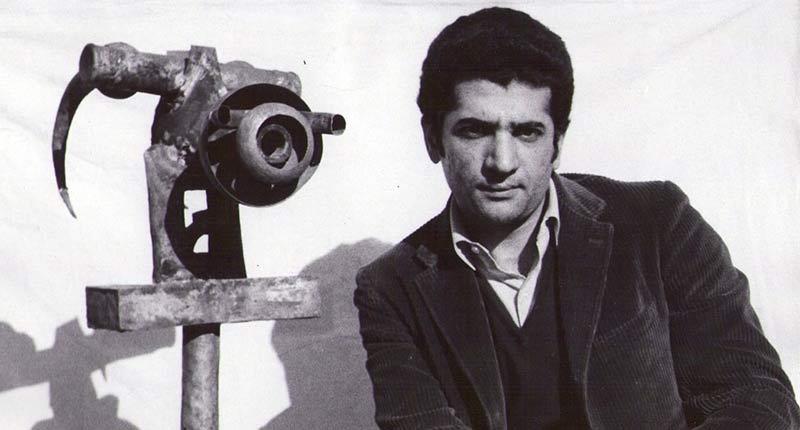

Tanavoli studied at the Tehran School of Fine Arts in the mid-1950s and then headed for Italy, immersing himself in European art and culture in Carrara and Milan. “My vision was very limited, and even though Carrara was a very conservative academy, I realised how behind my practice was, and how rich contemporary sculpture could be,” he says. In 1959, he graduated from the Brera fine arts academy in Milan.

Back at home in the late 1950s, there were his scrapes with the Ministry of Fine Arts, who kicked him out of a government-run studio. “I was making monstrous ceramics of animals that were considered avant-garde in their eyes,” he says, laughing.

This led him to a community of pottery shops and blacksmiths in the south of the city where local markets, filled with neon lights, shiny advertisements, locks, talismans and trinkets, fed into his vision. “Like Basquiat making art at another time and in another place, he roamed the streets of south Tehran in the 1960s, finding discarded objects,” Balaghi says. Pop art was making an impact, and seemed to chime with his mischievous, modernist sensibility. “Iranians have a sense of humour, and I found this in pop art,” he says.

The Saqqakhaneh school, which also included Hossein Zenderoudi, subsequently flowered in Tanavoli’s Atelier Kaboud workplace. This sparky new school fused avant-garde theory with Iranian folk culture motifs, producing a Middle Eastern strain of 1960s modernism rooted in popular culture.

The late US philanthropist Abby Weed Grey walked into the studio in 1961 and was instantly taken by the “brilliant colours and vitality of Tanavoli’s work”. She bought his gouache “Myth” (1961), marking the start of a pivotal partnership. Grey invited her protégé to the Minneapolis College of Art and Design in 1961, where Tanavoli was initially artist-in-residence and later a sculpture lecturer. She also founded the Grey Art Gallery in 1974; 25 works by Tanavoli drawn from this collection will be on display at the Armory Show in New York next month.

When Tanavoli returned to Iran in 1964, to teach sculpture in the Fine Arts Faculty of Tehran university, Grey funded a new foundry and ceramics kiln there — an act of generosity that still moves the artist. It was a surprisingly liberal moment for contemporary art: Tanavoli was even a cultural adviser to Empress Farah Pahlavi, the Shah’s wife, who was creating a fine collection of western contemporary work.

Since the revolution of 1979, however, his relationship with the Iranian authorities has been fraught. After being “blacklisted”, he settled in Canada in 1989, and visits Iran twice a year, moving back and forth like “seasonal migration”, he quips. In 2003, against all expectations, a show of his sculptures at the museum of contemporary art in Tehran drew record numbers of visitors.

But problems continue. He is caught up in a messy dispute with the city authorities of Tehran over ownership of 60 sculptures. Last year, the municipality, which he calls “hardline”, seized the works from his villa in a suburb of the capital; some ceramic pieces are now damaged, he says. His long-term plan is to reopen the residence as a museum.

It is hard to disentangle Tanavoli from the tumult of east-west relations and policies, a subject broached by Balaghi. “The last museum solo show of Tanavoli’s art was held in the US in 1976 [at the Grey Art Gallery]. Why the 39-year gap? Perhaps there is a resistance to looking at Iran beyond the frame of the strictly political, to seeing its people as having a diverse cultural life,” she says.

“There are some who consider Tanavoli an artist of the elites. Perhaps because his art fetches record prices at auction; perhaps because he has had well-placed patrons. But he has always gone against the grain and stayed true to his life-long path of seeking a productive space for humanity through his art,” she adds. It is a highfalutin’ claim — but one that rings true.