"Parviz Tanavoli: plenty of 'nothing' - exhibition"

By Shadi Harouni | The Guardian

10 February 2015

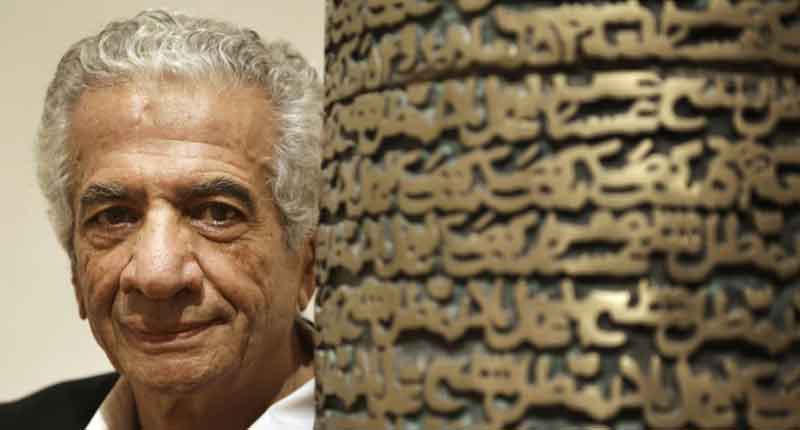

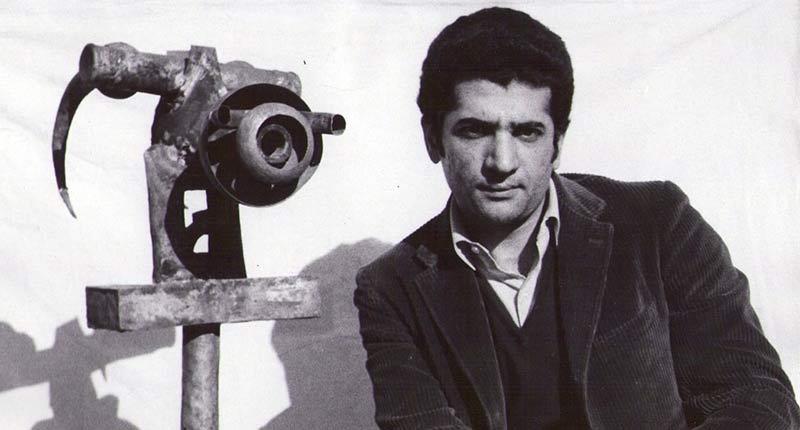

It is rare for an Iranian artist to be widely celebrated at home, withstanding the scrutiny of a nation in love with both art and the contemporary and yet highly critical of its living artists because it recognizes the contemporary as a category imposed from the outside. Born in 1937, Parviz Tanavoli has become a legendary figure through a prolific career as artist, scholar and teacher. Iran’s first significant modern sculptor, he works in a style distinctly his own, undeniably modern, and entirely Iranian.

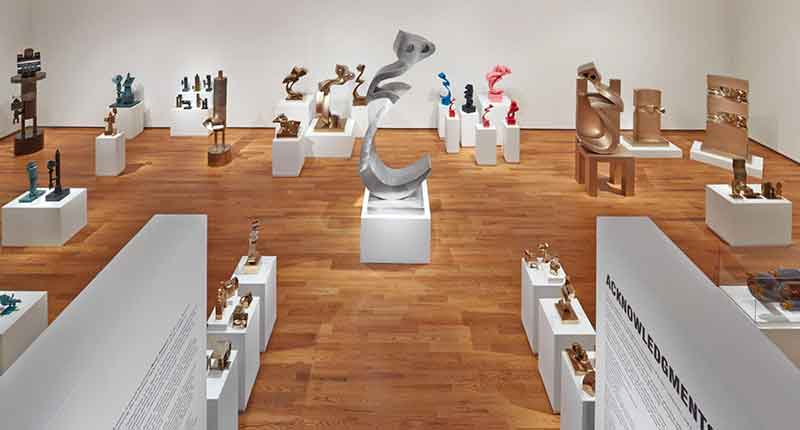

In bringing together over 50 years of his art in his first US solo museum exhibition, the Davis Museum has the task of engaging with thousands of years of cultural heritage, which Tanavoli draws on with fervour and ease. He neither imitates nor ignores the Iranian visual lexicon, but rather makes it his own and expands upon it.

Tanavoli is one of the handful of artists responsible for the Saghakhaneh style, which developed in the early 1960s as young, mainly western-educated artists sought to reconcile distinctly Iranian forms with the language of contemporary art. In doing so they turned to traditional forms, touching on pre-Islamic and Shia Muslim art and architecture, as well as Iranian folk motifs.

Among those associated with the style, Tanavoli’s work embodies the widest range of cultural signifiers, from the grandiose to the familiar, from the ancient to the now. His scholarship has been impressive in its scope and influence. Tanavoli has published books on locks, talismans, gravestones, horse and camel trappings from tribal Iran, rugs and textiles, make-up boxes, tablecloths, ceramics, and the magic of letters and numbers, among other topics. He is by temperament a collector, and the innumerable hours he has spent scouring flea markets, villages, and artisans’ workshops have deeply affected his work.

It is indeed often difficult to distinguish an established cultural motif from one Tanavoli has established. When one thinks of an Iranian form, one is as likely to visualise a Tanavoli as an ancient relief. The pseudo-cuneiforms covering his more recent Wall series are just as much etched into my mind as the 2500-year-old inscriptions on the side of a granite boulder at the foot of Mount Alvand in Hamedan province, to which I made weekly pilgrimages as a child.

As the country has grown more secular, Tanavoli has built up and maintained certain religious motifs as a significant part of his visual lexicon. A good example is his relationship to locks, as fastened by devotees to the lattice grillwork of Shia shrines.

He shows the same devotion to saghakhanehs, small niches in walls offering passersby drinking water in memory of Imam Hussein, who with his followers was cut off from water before his martyrdom at the battle of Kerbala in AD680. Tanavoli’s devotion to form while excluding function releases the artistic tradition from its mythical aura.

While the lock has been a site of both ingenuity and metaphor in Iranian heritage, it is Tanavoli’s sculptures and extensive research that make it so significant. He ties in religion, myth and history with contemporary hope. He equates the praying hands that fasten locks onto shrines with his own, which sculpt them in the studio, often as small breasts or disproportionate penises.

Tanavoli’s fervour for Iranian formal heritage is balanced by a sense of irreverence and play that give his work relevance beyond a specific cultural context. In Innovation in Art, 1964, he cuts a vaginal opening into a handmade Persian rug to make room for a toilet ewer, a scatological object most common and most rejected in the Iranian domestic psyche. The ewer is painted after a Jasper Johns Target and the intricate patterns of the rug are flattened into kitsch as they are crudely traced in paint.

His signature Heech series, which has for years been a staple of Tanavoli’s practice, was conceived of in 1965 as a protest. The three letters of the word heech, meaning nothing or nothingness in Farsi, took form in the decorative Nastaliq script both as a protest against the empty overuse of calligraphy in the increasingly popular Saghakhaneh style and the individuals, the institutions and the market that embraced this emptiness. The many years Tanavoli has spent with Heech, and the sheer number of pieces produced with his factory-like ambition, take it beyond the cynicism of its initial protest.

It is radical for an artist to make “nothing”. But Tanavoli’s heech is constant neither in form nor narrative. The pieces are made in all sizes and media, from bronze to fibre-glass and neon lights. Heech emerges from a box, melts into its chair, lies beneath a table and embraces another. As it takes form it grows both endearing and ridiculous. Its irony, not lost on the artist, points to his nostalgia for the figure, a need for play, for narrative, for history.

Tanavoli cannot stay on a heech hiatus. However freely he has drawn from and built upon his own heritage, he has always done so with great care. It is partly this sense of responsibility that has given him the popular status he enjoys in Iran. While it may be a source of pleasure and inspiration, it is no doubt also a burden for any artist, one he has borne seamlessly, and with grace and humility.