"Six Decades in the Making"

By Shiva Balaghi | Ibraaz

26 February 2015

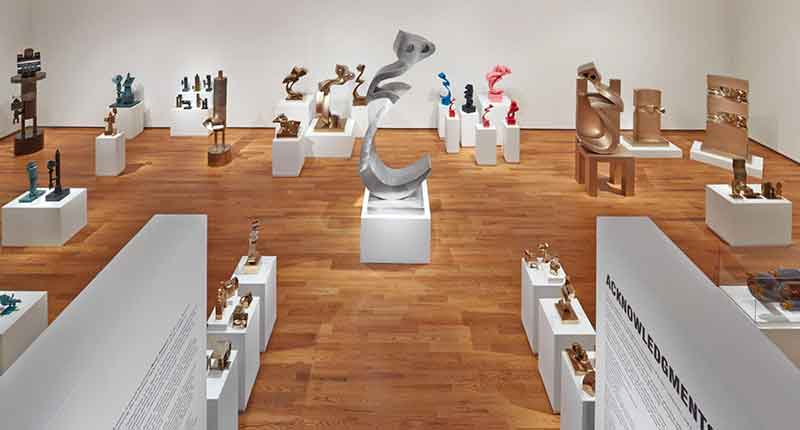

Installation view, Parviz Tanavoli, at the Davis Museum, Wellesley College, Massachusetts, 2015. All works copyright Parviz Tanavoli, image courtesy Davis Museum, Wellesley College.

Parviz Tanavoli’s Retrospective at the Davis Museum

When there was no modern Iranian sculptural tradition, Parviz Tanavoli invented one. When there were no exhibition spaces dedicated to exhibiting modern Iranian art, Tanavoli organized a show in the marble lobby of a bank. When there were no artist spaces for Iran’s contemporary artists to gather in the 1960s, he worked with his friend Kamran Diba to open Club Rasht. And when American audiences had never before seen contemporary Iranian art, Tanavoli rolled up fifty works by fourteen artists and carried them from city to city across the US from 1962-65. The career of Parviz Tanavoli has been marked with imagining new artistic horizons and creating new possibilities for studying, making, and exhibiting Iranian art.

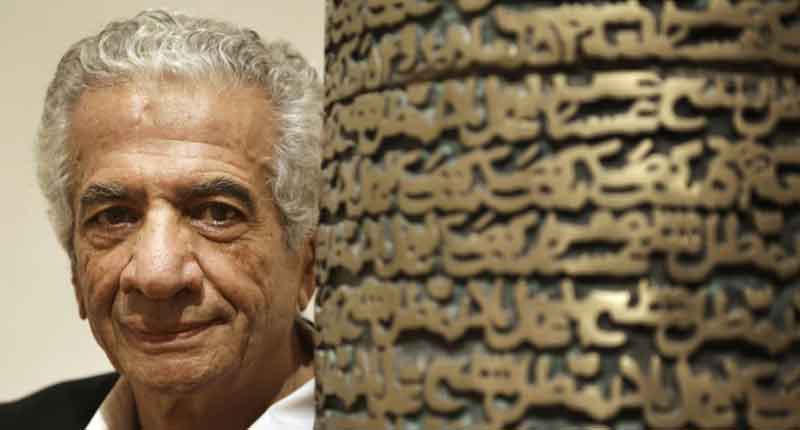

An artist, collector, curator, scholar, and teacher, whose career has spanned nearly six decades, Parviz Tanavoli is one of Iran’s most influential artists. On February 10, 2015, Parviz Tanavoli, the artist’s first comprehensive retrospective exhibition to be mounted in a U.S. museum opened at the Davis Museum of Wellesley College.

Curated by Lisa Fischman, director of the Davis Museum, and myself, the show includes over 175 works of art. Though Tanavoli is known primarily as a sculptor, the show also features works across various mediums including lithographs, prints, paintings, ceramics, neon works, and jewelry. We drew our curatorial inspiration from the way Tanavoli exhibits his art in his own home, organizing the works thematically and chronologically. Sections of the show are devoted to recurring motifs in the artists’ work such as Heech, Farhad, the Poet, and the Wall series.

The landmark exhibition is the inaugural event of the Maryam and Edward Eisler/Goldman Sachs Gives Fund on Art and Visual Culture in the Near, Middle and Far East. Established in 2014 by Maryam Homayoun Eisler (an alumnus and Trustee of Wellesley College) and Edward Eisler, the Eisler Fund creates a cross-disciplinary platform for research, exhibitions and scholarship on art and visual culture within the Davis Museum and Wellesley College Art Department. True visionaries, Fischman and Eisler have collaborated to create the first such program at any university.

This exhibition offers students and faculty at Wellesley and nearby universities the unique opportunity to learn from Tanavoli’s rich body of work to gain insights in the complex process of making art but also the ways one can use art as a historical document. Tanavoli’s works offer a unique record onto the history of modern and contemporary Iranian art. On the occasion of his first solo exhibition in the US in nearly 40 years, I spoke with Tanavoli for Ibraaz.

Standing in the midst of some 4000 square feet of gallery space devoted to his retrospective, Parviz Tanavoli is clearly moved by the site. He made some of the works on display as an art student in the 1950s; other works are so new, they arrived at the museum directly from the foundry. Parviz is giddy, and every few minutes, he snaps another photo with his cellphone. I ask him how the show looks from his point of view.

‘Oh I tell you, I cannot believe it. I see all of my works from the last sixty years together, because this doesn’t happen very often. Some of these works are coming from other collections and museums. To see them all together, it’s amazing. I cannot express how it feels. I’m very happy to see them.’

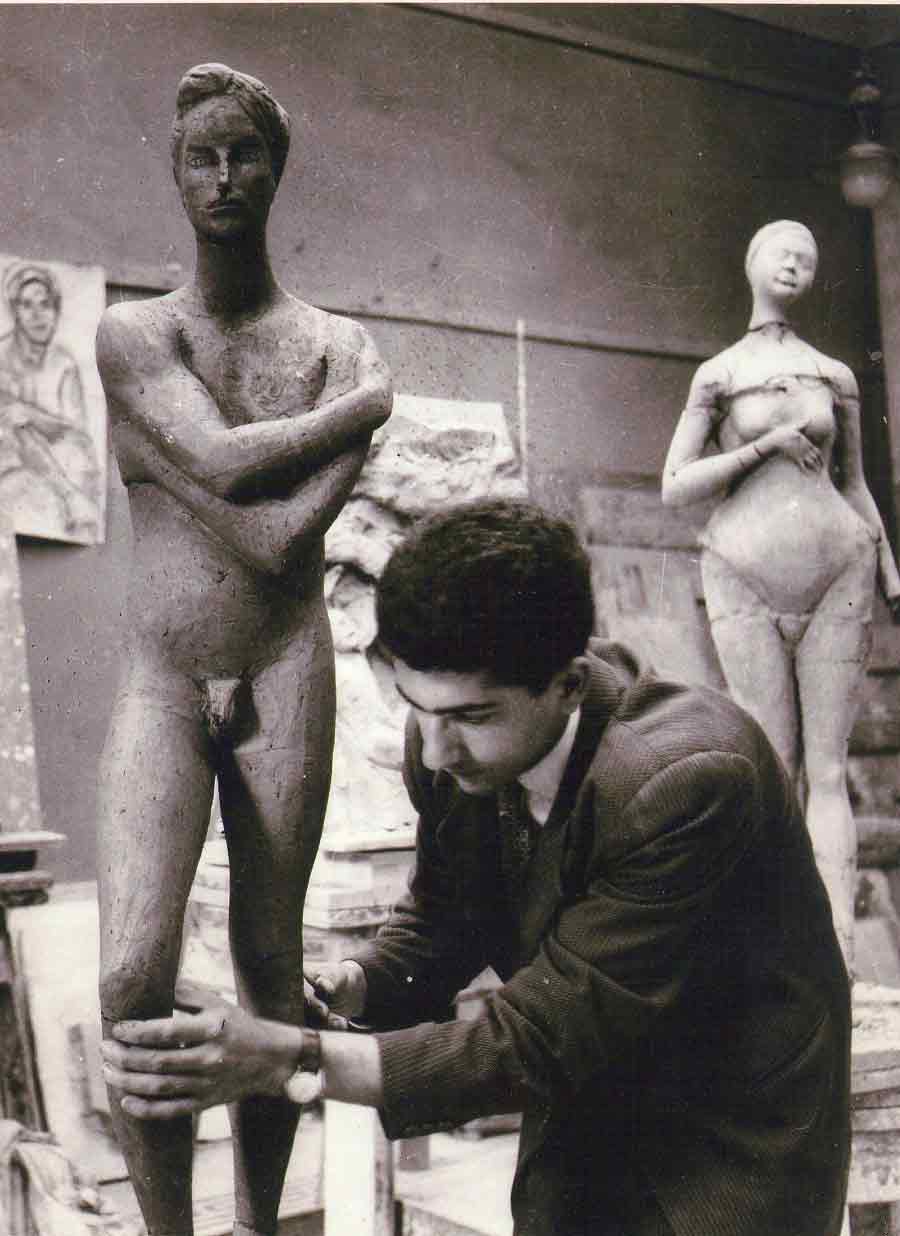

Parviz Tanavoli as an art student in Carrara, 1957. Courtesy of the artist.

As we were preparing for the opening, I’d check in regularly with Parviz. One night as the opening drew near, he said, ‘I’ve waited for 25 years and then the doors opened.’ I asked him to explain what he meant by the comment.

‘With the background I had in the US, I expected that doors would never close on me because from a very young stage in my career, I had shows in the States. I created a lot of my work in the US. I taught at the Minnesota College of Art and Design. I had a following in the public in the US, I was known there. Then all of a sudden, with the Iranian revolution and the war and the hostage crisis, they closed all the doors. The relations between the two countries were tarnished and I couldn’t continue. I lost all my connections. I went into the dark.

‘So when Maryam Eisler wrote to me to propose an exhibit at the Davis, I was very happy. I was waiting for the doors to open for me once again – especially in the US. For the last 25 years I have been living in Canada. I have come back to the United States, but I haven’t had any [solo] shows. And now to have a major show like this, is a great and very memorable event.’

As we walk through the show, Parviz points to a ceramic work from 1969 titled, Fallen Farhad. The work echoes drawings he made as an art student in Italy in the 1950s, when he trained with the famed sculptor Marino Marini. Despite being immersed in such a rich cultural milieu, Tanavoli recalls, ‘Iranian themes had possessed the very fiber of my being and haunted my thoughts.’ As a sculptor, he was searching for a style that reflected his heritage – but there was no tradition of Iranian sculpture he could rely upon. Ultimately, he found his answer in the character of Farhad, the mountain carver, from the epic poetry of Nizami.

Farhad has for the past six decades remained an inspiration for Tanavoli. Farhad was the ultimate artist, driven by passion and dedicating his life to his project of carving the mountain in hopes of gaining the companionship of his beloved Shirin. For Tanavoli, Farhad is more than just a muse – he is a symbol of a certain kind of humanity. ‘Beside his artistic qualities,’ Tanavoli reminds me, ‘Nizami describes Farhad as a super strong man, a man that could lift Shirin and her horse on his shoulder’s and carry them along mountain paths.’ This mythical character – who symbolizes dedication, devotion, sacrifice, and compassion – is more than a simple icon for Tanavoli. Farhad has become his artistic foil, his constant companion throughout his career.

‘When I left Iran to emigrate to Canada in 1989, I took this Farhad with me. I’ve just always had this piece in my home; it’s special to me. I carried it in my arms and bought it a ticket so I could sit the sculpture in a seat next to me on the airplane as we flew out of Tehran.’

The transition to life in Canada proved difficult for Tanavoli. ‘I thought my artistic career was over. I thought I was forgotten,’ Tanavoli told me. ‘We were living in a rental home, and I was a bit down and uninspired. Then, one day, one of my students came to visit me. Instead of flowers or sweets, she brought me a box of clay. This was just what I needed. I started making small sculptures with the clay.’ Tanavoli eventually established a studio and now travels between Tehran and Vancouver, making art in both cities.

Since then Tanavoli has returned to making art with a furious passion. He has had solo exhibitions at galleries in Tehran and Dubai; he has been part of important group exhibitions at NYU’s Grey Gallery, the British Museum, and the Asia Society. In 2003, Dr. Sami Azar, who was then the director of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art [TMoCA] curated Tanavoli’s first ever museum retrospective in Iran.

‘That was the most extensive show I’ve ever had,’ Tanavoli tells me. ‘Dr. Sami Azar called me out of the blue one day around 2002 and asked me if I’d like to have a show in the museum. That was a complete surprise.

‘At that time, all my major works were in Vancouver. We took everything back to Iran, and we exhibited it. I was worried because I thought I was forgotten. Who is going to come and see my show, I wondered, because my name had been wiped off of everything in Iran. But a lot of the young generation came to see the show – there were record numbers of visitors. My show took up nine galleries and even some hallways in the museum. I had accumulated so much art that no one had seen. Buses came from provinces – from Tabriz and Qum and Shiraz. There were young students who came on school trips. Anytime of the day that you went to the show, it was crowded. The museum felt like New York’s Metropolitan Museum; it was always full of people.’

Parviz Tanavoli and I walked through the ‘Heech Garden.’ Early in in our planning for the exhibition, my co-curator Lisa Fischman conceived of the idea of a Heech Garden, featuring sculptures of various colours and sizes. This display of nearly 30 Heech sculptures commemorates the 50th anniversary of the Heech, which has become iconic in the art world. Tanavoli has told me the idea of Heech or ‘nothingness’ came to him in the quiet of his studio, Atelier Kaboud.

‘Yes, the birth of Heech was towards the end of 1964, the beginning of 1965. It didn’t come accidentally, absolutely not. I wanted to make something that didn’t have a body that was completely different – not only from mine but from any sculpture. This occupied my mind for a long time. It’s very difficult when you ask your brain to give you an image of nothing. I mean the brain is incapable of it. You understand? And so it kept me busy for some time and occupied my mind. I knew there should be some way of finding this. At last I wrote it down. And I thought wow – how about the letters of the word itself.

‘So I started from there. My first Heech was a relief that hung on the wall – it was made of plastic and some other materials. And from there I made the first three dimensional Heech, which became like my classical Heech. They are just a legible Heech, a standing figure that is recognizable to everyone. But then I made Heech in other ways, among them Heech lovers. Heech became for me like a being – and I thought Heech cannot always stay alone. It has to have a mate and has to have a lover. I matched them together, put them together. And I thought ‘My gosh, they look good together.’

‘So I practically exhausted anything that could be done. I combined my Heech with furniture, with chairs and tables, put it in the cage and out of the cage, on the wall and so forth. It occupied my full life for seven years. And then at the end of the seven years, I couldn’t seem to get away from it, but decided I have other ideas and I moved on.’

I spoke to Tanavoli about the symbolic importance of the letter ‘h’ in Perso-Islamic culture. We refer to the Persian letter as the ‘two eyed heech,’ so there has always been an anthropomorphic quality to the letter in Iranian literary and visual culture.

‘Exactly,’ Tanavoli responds with his characteristic enthusiasm. ‘Yes, I mean the figure of the Heech to me was like a being. To me, it resembled a human being, with no gender. Some people ask me is your Heech a female or a male. I mean sometimes it can be a female, the beloved, and sometimes it can be a male, the lover. It doesn’t really matter. It has a head, a body. It’s a very graceful figure, with its elasticity. It moves practically like a human body. It was just the right shape for me.

‘And then all the meaning behind it. Don’t forget, there’s an ocean of meaning behind it. Not just me but it occupied the minds of Persian poets for a millennium. From Khayyam to Hafez and other poets – all questioning nothingness. Is there truth in the thing or truth in nothingness – and how are they together? Which one is really the one we should become attached to? Rumi says, ‘Abandon that which looks like something but is nothing. Seek that which looks like nothing but is something’.’

Parviz often recites poetry when he tries to explain his art. Your art, I tell him, lives in Persian poetry.

‘Yes, that’s very true. That’s really my life. I live with these things. It’s not just about my time in the studio. The rest of the day, these ideas follow me. A verse of poetry sometimes follows me for days and days. I live with it. And when I go to the studio of course these thoughts don’t disappear – Persian art, Persian poetry, the pictures I have seen. Even the scenery of every day life – the bazaar, the people. It stays with me.

‘And another thing that I very much enjoy is the art of the people – I mean something that is not intended to be art, but it is improvised art by ordinary people in the bazaars, in the streets, in society. I love it. I enjoy it when people simply express themselves by mounting some signs, some writing. The way they mix colors. They don’t follow any rules or regulations. These are very inspiring to me.’

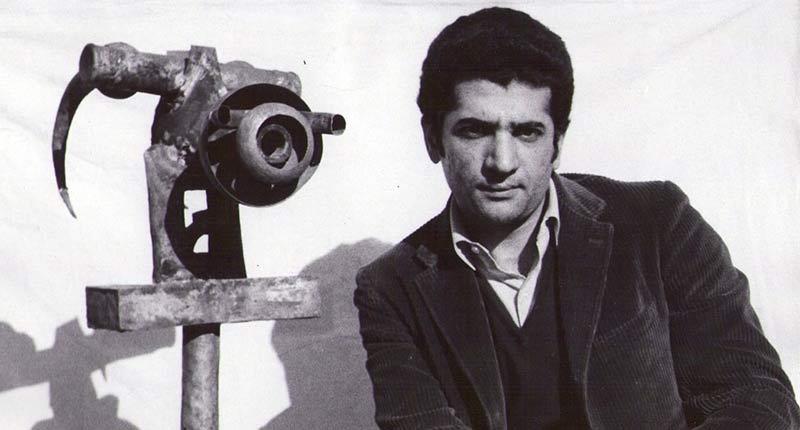

This propensity to find artistic inspiration in the quotidian leads me to ask Parviz about the saqqakhaneh school. The term was first coined by the art critic Karimi Emami and Kamran Diba, the founding director of TMoCA, likened it to a kind of spiritual pop art. When he returned from studying in Italy, Tanavoli spent a lot of time walking around the bazaars and neighborhoods of South Tehran. He studied the architecture of Shiite devotional spaces – the saqqakhaneh and emamzadeh – fountains and shrines. It was at this point that Tanavoli began to make his formative contributions to the saqqakhaneh school. I ask Tanavoli whether one can use the term and apply it to his art.

‘From 58 to 62, that was the genuine period of the Saqqakhaneh School – and I was a part of that, I don’t deny it. I was very instrumental to that movement. But later when everyone else jumped on the wagon and followed, then I purposely tried to keep away from it. But the ideas that appeared to me or those ideas that started in 58-62, they never left me. These ideas remained with me, but to me they are a lot more than just saqqakhaneh. For example, Heech has nothing to do with saqqakhaneh. Or some of the artwork that I did under the influence of Pop Art.’

There was a time in the early 1960s, when three leading Iranian artists – Parviz Tanavoli, Siah Armajani, and Marcos Grigorian – lived in Minneapolis. The three became friends and sometimes exhibited their art together. I asked Tanavoli if this was the time when Pop Art influenced his work.

‘The three of us met regularly and talked. Marcos was a stubborn man. He was totally against Pop Art. He was a big believer in Abstract Expressionism. Armajani and I were pro-Pop Art. We loved it. Pop Art was the talk of the day. We got into some serious discussions about these issues. To us, it was all very exciting.’

I ask Parviz to talk a bit more about the influence of Western art on his own art practice. Though he lived in both Italy and the US, studying and teaching art, it strikes me that his art remains so closely bound to Iranian motifs drawn from poetry, folk culture, ancient ruins, tribal art. He is an international artist in that his critical engagement with the arts has always crossed borders; his art is housed in public and private collections across the Middle East, Europe, and the US. And yet his art remains recognizably Iranian.

‘Some years ago, people told me you are wasting your time. You should be a part of international family and make art like everybody else does. Why do you keep making art that is Iranian, influenced by Iranian poetry and history? They told me, Westerners don’t understand it, and why are you insisting on making this kind of art? But I replied: Well, maybe they should understand it, maybe they need to take the time to understand it. I cannot do anything else. Anytime I go to my studio, I always come up with something Iranian. My art always has a taste of Iran. It’s not up to me; it doesn’t depend on me. That’s how it happens. I have learned how to make Western art, both academic and modern and abstract art. I teach it to my students - I let them do it if they want, I don’t stop them. But when it comes to myself, I just can not do anything else.’

Shiva Balaghi is a Visiting Scholar of Art History at Brown University. Together with Lisa Fischman, she curated Parviz Tanavoli, on view at the Davis Museum at Wellesley College through June 7, 2015.